Unathi Kapa shares a story that’s about much more than food, and reflects that it is through woven words and food that she hangs onto her father’s memory.

My father was the first to bravely volunteer his belly as a testing ground for my novice cooking. Mama was out of town. Rather, out of the village; and she would only return home the next day. Tata, with what I deduced to be a mischievous smile, posed a question he had never directed towards me ever before: “So, LhoLho, what are we having for supper tonight?” At least he was addressing me by the special nickname he had assigned me. We were still on familiar ground.

I was promptly rendered flaccid by the weight of the question and the fact that I was absolutely clueless how a twelve-year-old was to manage putting a meal together for her much older father, who happened to have a reputation for low tolerance of poor performance in anything in life. Plus, Tata was a good cook. I had savoured his meals and concluded that his dishes were more delicious than the ones Mama had prepared with love but ended up boiling the flavour to death, information which I kept to myself.

What business did I have, critiquing my mother’s cooking, anyway, because, though a lauded learner at school, word in my family was that I was spoilt beyond redemption by my same mother, with a bleak outlook in any domestic future endeavors and therefore I was certain this was a task I would fail dismally. So, I smiled, as I always did through all nerve wracking moments in my life.

Never to utter words such as “I can’t” and not yet accustomed to responses like “Please excuse me but that falls outside of my skill set”, I smartly settled on what I deemed would be the least challenging meal - sausage and brown bread - both from the shop that my very same parents owned. This also happened to be the location in which we stood as Tata posed the earth-shattering question that late afternoon.

At least I could boil the sausage and the bread was already sliced, thanks to Albany bakery and their colourfully wrapped truck that conveniently delivered warm loaves of bread all the way from Queenstown, some forty kilometers to our home village. I did not have to bake bread from scratch. Phew!

My father, a proud, strong Xhosa man, born and bred in Hekeni, the village that nurtured him as a boy, which he now frequented to visit his elderly mother, was teacher and school principal by day, and while marking school assignments by night, I often hovered curiously observing every stroke or ribbon of red ink on white paper. I had not done the same with his cooking. A missed opportunity.

Until now, I also had never seen him eat bread for supper. We always had a full, cooked meal consisting of a variety of vegetables, rice and some form of meat, followed by dessert. But I was not about to set myself up for failure by offering any such delicacies.

Every evening, our father sat and watched television and enjoyed supper with us, his wife and children, as soon as they locked the doors to the bustling Sunrise Store. News at 7 o’clock on SABC was not to be missed.

“...food always featured prominently at cultural gatherings in our home, as large enamel bowls sprawling with white samp, freshly slaughtered beef and colourful vegetables were passed around...”

On this night, when we happened to be all by ourselves as he eventually dug into my sausage, and he beamed with pride complimenting my cooking, he was not Tishala [Teacher] as many addressed him, in our home village and beyond - he was my Dad. Complementing. Affirming. I had passed this first crucial test of my culinary capabilities but I’m still not sure if it was with flying colours. I had not yet learnt that one should not add salt to sausage. And Tata never mentioned it.

A devout traditionalist who performed his customs religiously with extended family and our fellow villagers in attendance, Tata ensured that food always featured prominently at cultural gatherings in our home, as large enamel bowls sprawling with white samp, freshly slaughtered beef and colourful vegetables were passed around, and umqombothi sorghum beer flowed freely, accompanied by spirited song in the euphoric air, my young soul transported. Abundance of food, to me, smells of love and community. It reminds me of being safely home.

When Tata retired after over forty years of teaching, we were to relocate from our village home to a farm he and Mama had recently purchased - to fulfill my father’s lifelong dream of owning a swathe of land. Mama spotted the property up for sale in the Daily Dispatch newspaper and wanted to jointly fulfil her beloved’s desires, I would later learn.

When we packed up and moved to the faraway new place, I did not know what to expect of Tata’s newly acquired title of Farm Owner. Who would he be post-retirement, without his red pen? I would soon discover that he was still just our father as he didn’t even put up a sign at the farm gate with the family name, to mark territory.

“...I was awestruck as I watched him in our kitchen kneading dough with such care, to perfect elasticity, and rising to the occasion, transforming to fluffy oven-baked loaves of bread..”

But I was pleasantly surprised to learn that he would now thoroughly enjoy cooking. Some Sundays he slaughtered a chicken raised on the farm, cooked it outside the house on an open fire in a three-legged cast iron pot and brought it in to be served on the set dining table with the rest of the food that I or Mama would have cooked on the gas stove.

I was awestruck as I watched him in our kitchen kneading dough with such care, to perfect elasticity, and rising to the occasion, transforming to fluffy oven-baked loaves of bread. It was a mesmerising time. Until the stroke struck my father, and debilitated the very hand that I had watched weaving all kinds of magic in my life. Never to recover.

But this time, I had watched and committed every ingredient and measurement to memory. I would soon step into the role of kneading and serving Tata “delicious bread”, as he later remarked, at a time when he couldn’t even tie his shoelaces. A great honour.

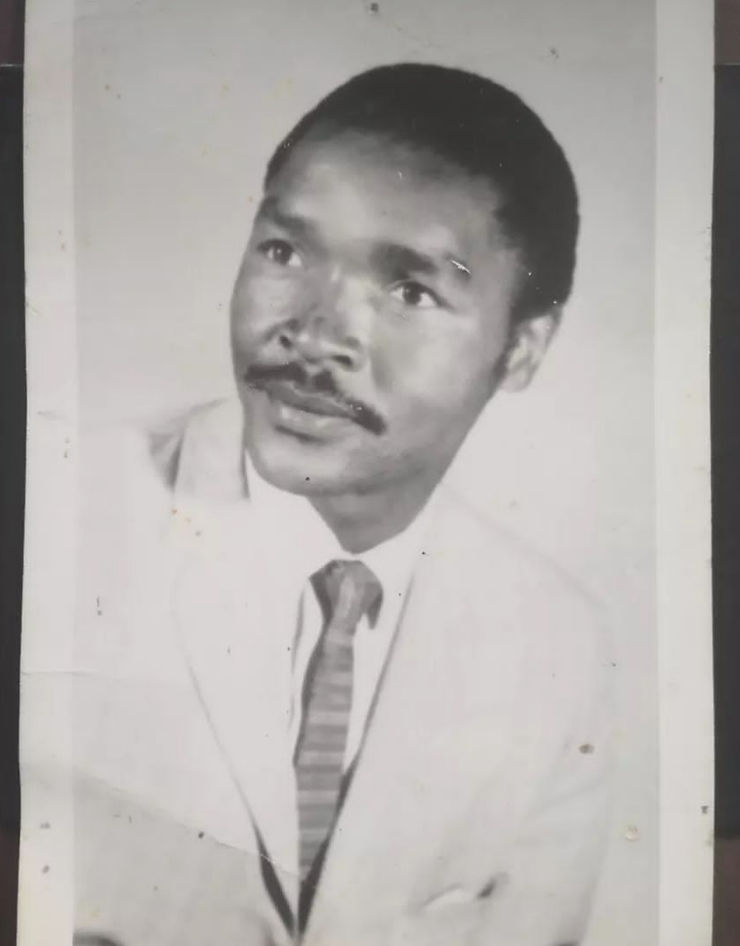

I suspect that my storytelling, which often centres around my father, whose only bond we shared was love, as I do not carry his blood, is my subconscious attempt to clutch onto his memory. For, the only two photos I have of him do not quite afford me the luxury that my potpourri of images amassed over 10 years since my induction to social media do. I hang onto his memory through woven words. And food.

While the most perfect sausage still eludes me, I now approach peaches, sweet melons, prickly pear, blackberries, blueberries, cherries, oranges, naartjies, plums, white and black grapes, watermelon, with nostalgic reverence, because Tata always bought these fruits and more in boxfuls, just for his family's indulgence. And I never miss an opportunity to tell my daughter that God loved us so much that he gave us colourful fruit.

Thanks for this heartwarming story